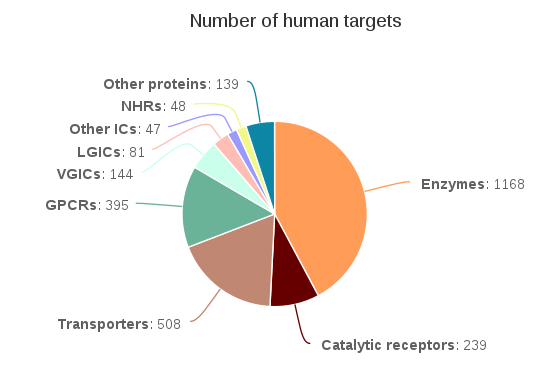

This is an introduction to resolving bioactive ligands and their protein targets from the literature. It includes their conversion to standardised molecular identifiers so these can be communicated to the Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (GtoPdb) team.

(n.b. identifying what is already captured in the database is addressed in this tutorial).

The utility is conceived for three groups:

1) NC-IUPHAR Committee members updating target families in GtoPdb;

2) Authors and publishers who are (or considering) incorporating GtoPdb links into manuscripts;

3) GtoPdb users who would like to directly recommend new content (including their own papers).

This outline extends from the minimal requirement of identifying the document, to a complete set of specifications that can be directly entered into the database. It is envisaged that contributors can send us comments and cross-references that extend the basic identification. The curation team will then select entries for curation but we use the comment fields to add contextual annotation. This expert distillation adds unique value to the database.

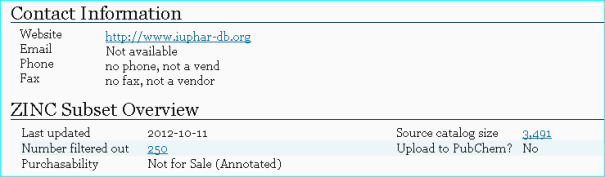

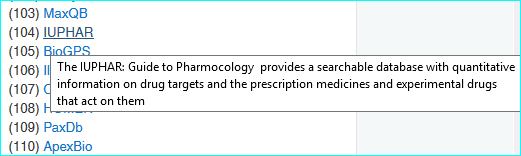

While we do not claim perfection, GtoPdb exemplifies not only comprehensive entity resolution but also highlights ambiguity (e.g. in curator notes). This introduction assumes basic familiarity with chemical structures and protein sequences. In addition, we recommend pharmacologists increase their familiarity with PubChem and UniProt in general, since these are key resources that GtoPdb links out to (n.b. molecular resolution is important both to extend the understanding of the papers you read and those you might write or referee).

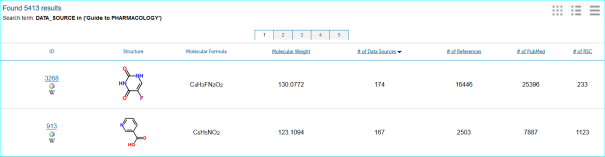

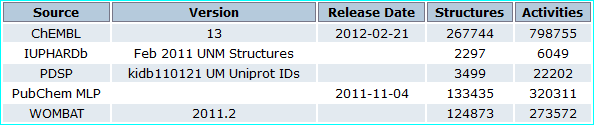

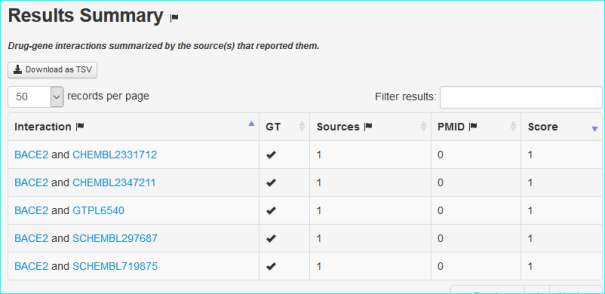

The concept of reading a journal paper “D” that describes an assay “A” with a quantitative result “R” for compound “C” that modulates the activity of a target protein “P” is familiar. While it does not encompass all permutations, the relationship can be expressed in shorthand as “D-A-R-C-P” (PMID 21569515). The GtoPdb curation team have converted 1000s of these relationship chains into structured database records. The shorthand can also describe variants, such as A-R-C-P for PubChem Bioassay or matrix screens (i.e. without D since A-R is web-based), C-P for DrugBank-type target annotation (i.e. no direct D-A-R) and agents with unknown mechanism as D-A-R-C (i.e. no P). Inspection of different GtoPdb entries gives an idea of how we populate database records and practical ways of resolving the ligand and target (i.e. C and P) entities are described below. Importantly, identifications are best communicated to us as URLs since this is less error-prone (i.e. rather than typing out a chemical or protein ID number, just copy-and-paste the primary URL). As an example, we can use a paper on the AstraZeneca clinical development compound AZD9668.

Document. While we can resolve the A-R-C-Ps within a new journal paper, the more our collaborators can do in advance the better. Thus, a PubMed number (PMID) for “D” is convenient since this can be a URL. A DOI will also do (but check it works please). While a traditional citation is acceptable, this should include the full title. Googling this is likely to find a URL from PubMed, PubMed Central, EuropePMC or the publisher’s site with a DOI. The curation team also have CiteUlike accounts so we would be pleased to accept input in this way, since copying over a reference is thereby error-free, automatically out-linked and gives you the facility of adding collaborative notes (including entity identifiers). Note also we include links to some non-journal “D” types, but we expect you to judge the provenance of non-peer reviewed sources. Patent numbers are useful but you will need to establish that the document actually contains A-R-C-P relationships (but we can advise on this). As a search term in PubMed, AZD9688 returns 9 papers but the first of these “AZD9668: pharmacological characterization of a novel oral inhibitor of neutrophil elastase” is a likely candidate for extraction of the primary data for this lead compound.

This “D” could thus be communicated to us as either;

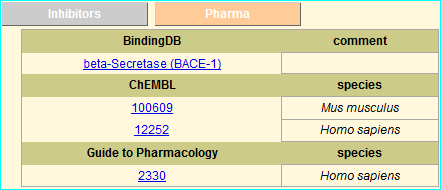

Assay. The specifications of assay conditions are not extensive in GToPdb, since we provide the reference wherein these are described. However, it is useful to us if you highlight relevant sections from the paper (or paste into CiteUlike notes). This helps us specify the molecular mechanism of action (mmoa), either implicitly (e.g. the target is identified in a different section of the document) or explicitly (e.g. competitive inhibition or partial agonism is specified). In the AZD9688 example conditions are described in Materials and Methods, The section starts with “The potency and selectivity of AZD9668 were determined by measuring the cleavage of peptide substrates to products by a range of serine proteases…” Note that extracted summary assay descriptions and results from the same paper may surface in multiple places on the web (e.g. ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay BindingDB and BRENDA). These cannot be expanded on here but they can differ in descriptive text.

Result. This needs to be expressed as a standard parameter such as IC50 EC50, Ki, Kd etc. We typically report these as written in the paper, but convert concentrations to nM and then log these to pAct (so if you come across ug or ng please do the nM conversion). Note we round down reported results where they clearly exceed the significant figures appropriate to the experiment (i.e. typically two or three). In the AZD9688 paper we find a detailed description“AZD9668 had a high binding affinity for human NE (KD = 9.5 nM) and potently inhibited NE activity (Table 1; Fig. 2). The calculated pIC50 (IC50) and Ki values for AZD9668 for human NE were 7.9 (12 nM) and 9.4 nM, respectively. In addition Table 2 includes a log transformed Standard Error of the Mean as a pIC50 of 7.9 ± 0.12.

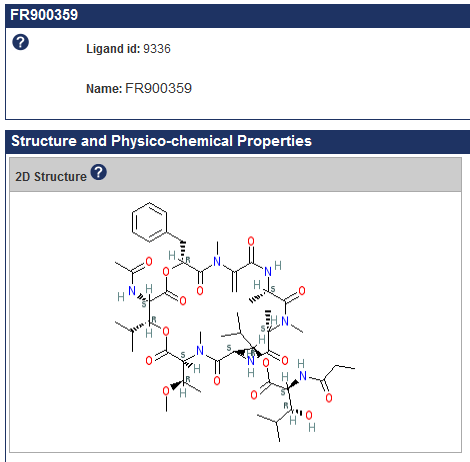

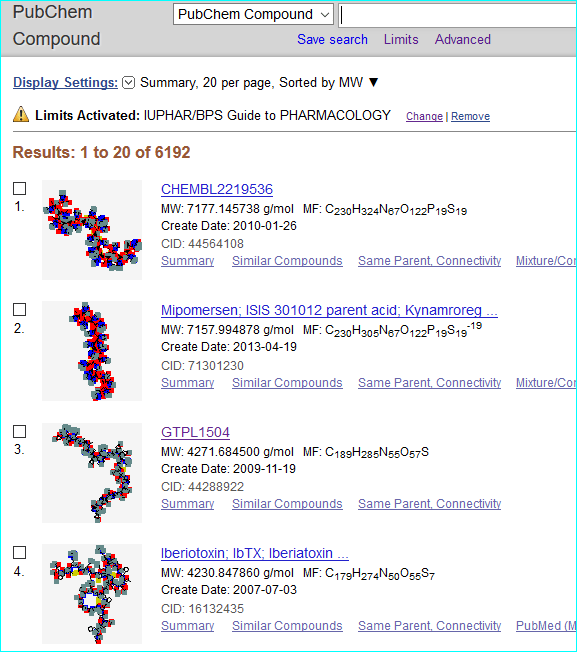

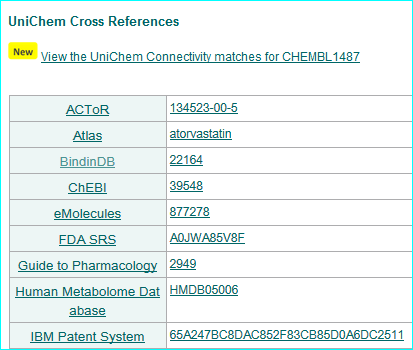

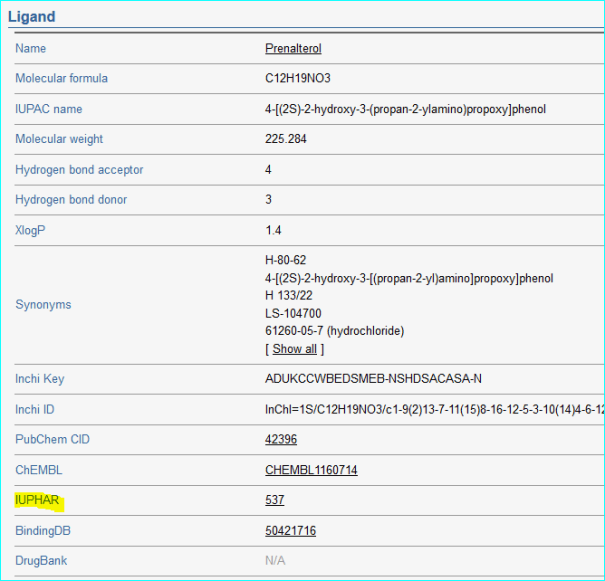

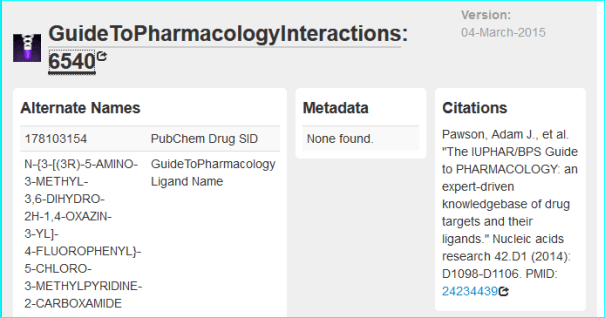

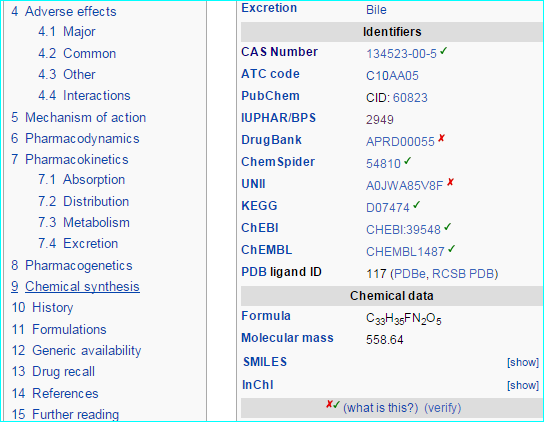

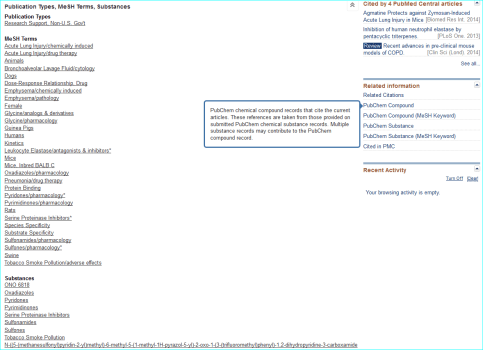

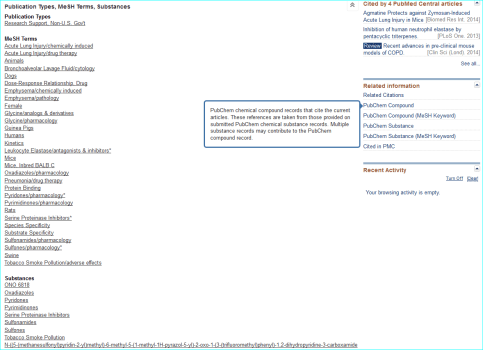

Compound. Public database chemical identifiers (e.g. PubChem, ChemSpider, ChEBI, DrugBank or ChEMBL) or commercial ones (e.g. CAS registry numbers) are not yet widely used in papers. For medicinal chemistry journals in particular, structures can be obscurely labelled in SAR tables as “11h”, or even as Markush-type enumerations. However they are usually made explicit via structure images in Results and/or as IUPAC names in M&M. Where names are used for “C” the following are useful a) a shorthand biochemical name b) a company code name c) an INN or d) an English/US brand name. For a PMID MeSH can be a useful first-pass for entity resolution. You can inspect this by opening up the terms under the PubMed text and also see what is linked under “Related information” on the lower right of the page. The links for the AZD9688 paper are shown below.

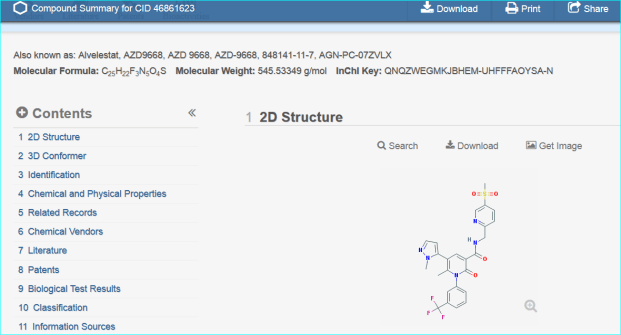

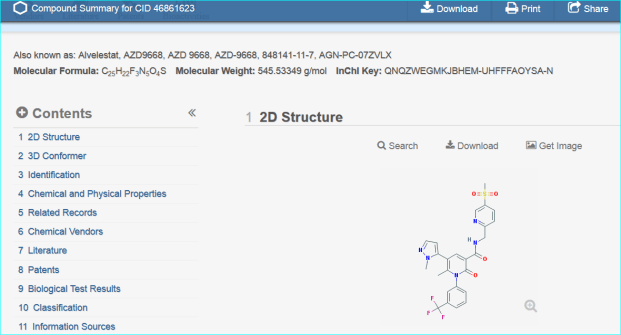

Exploiting MeSH within the NCBI Entrez system cannot be expanded here. However, familiarisation helps you with entity nomenclature choices (since it is part of what MeSH annotators do) but the specificity is somewhat patchy due to various types of false-positives and false-negatives. Notwithstanding, this paper is a successful example, since the PubChem compound link takes you directly to CID 46861623

The resolving operations for chemistry can be termed name-to-structure (NTS). This is particularly challenging where queries in chemistry sources retrieve different structures for the same text name, or in the case of company code names, sometimes no structure at all (see PMID 23159359). However, in PubChem, an empirical guideline is if a large number of submitters agree on the structure (i.e. many substances merged in the CID) and the names in multiple sources match, both strucuture and name may be correct. If you draw a blank in PubChem you can try the NCBI “all database” Entrez search (e.g. with a code name) that includes PubMed and PubMed Central. Note that Google Scholar may give true hits not found in NCBI Entrez since it indexes text from behind some publishers paywalls. Those of you with access to SciFinder may occasionally find NTS matches (performed as a concept search) not in Entrez or Google Scholar.

Good papers elinate the equivocality of “C” by descriptions of either a) a 2D image, b) IUPAC systematic name (sometimes in supplementary data) c) SMILES, d) InChI string or e) an InChIKey. You can send us any of these but it is better to resolve them to database IDs yourself by any of the following routes;

- Search PubChem via SMILES, InChI string, InChIKey, .SD or .mol file

- SciFinder search with SMILES or InChI string to resolve a CAS No.

- InChIKeys can be rapidly checked in Google (PMID 23399051)

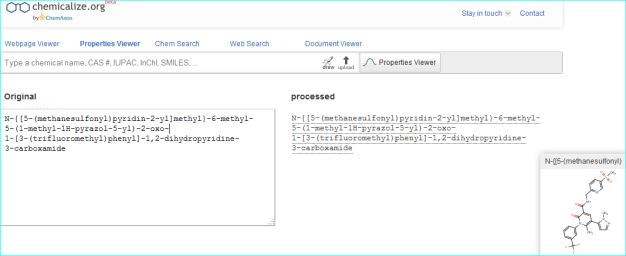

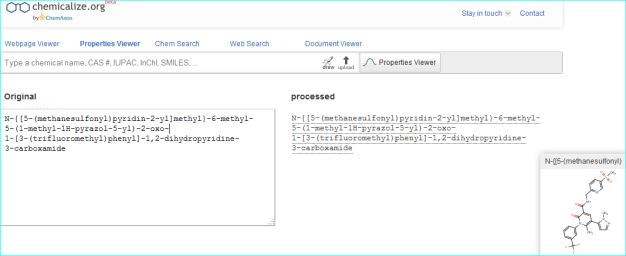

- IUPAC names converted to structures using chemicalize.org or OPSIN

- Images extracted to structures with OSRA.

- Use a chemical sketcher that outputs a structure

The AZD9668 paper is an easy case, since it exemplifies the structure as an image, an IUPAC name, along with the INN link for alvelestat.

As an example, we can corroborate the structure by automated conversion of the IUPAC name using chemicalize.org.

These two routes to chemical entity NTS resolution concur with a third result, a direct PubChem search for “AZD9668” shown below.

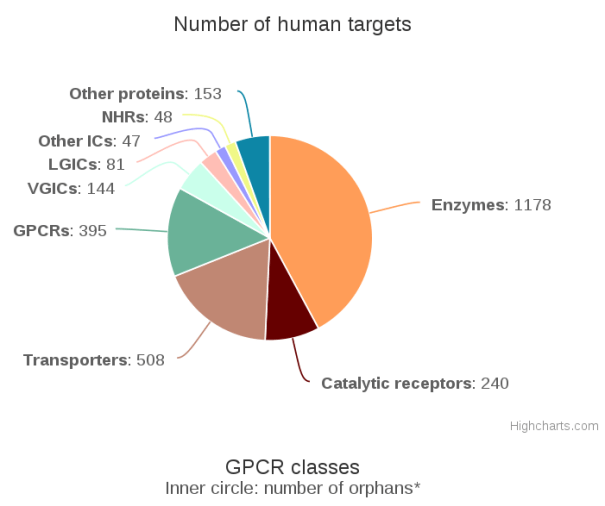

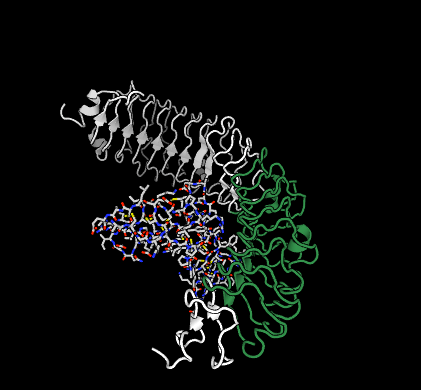

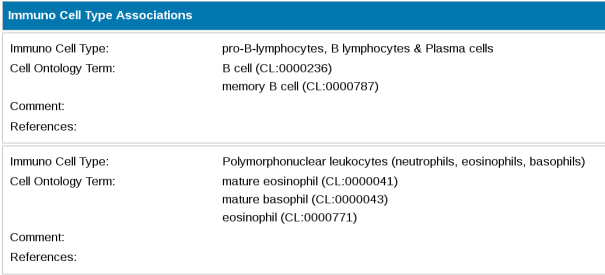

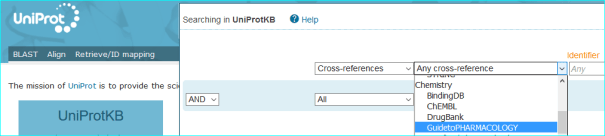

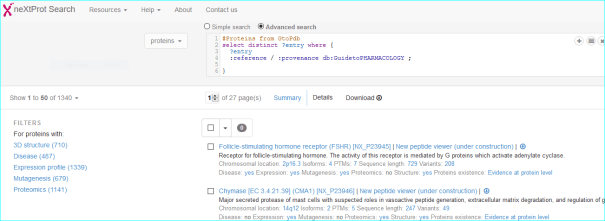

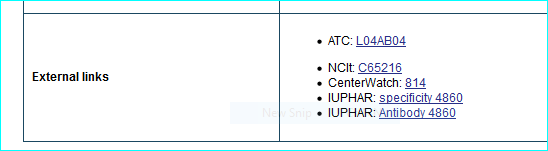

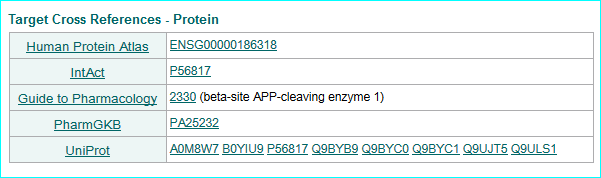

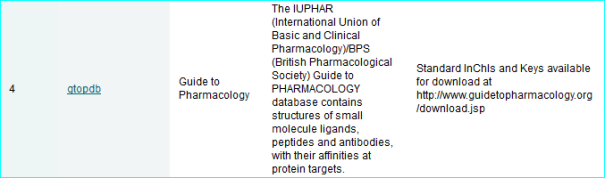

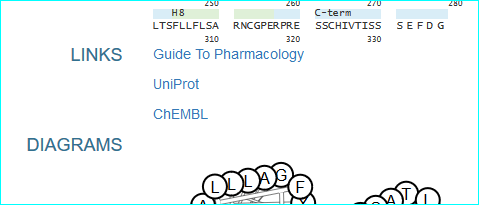

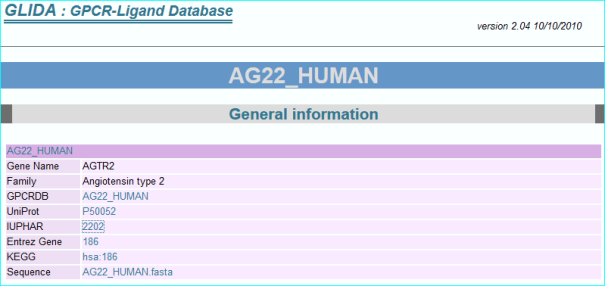

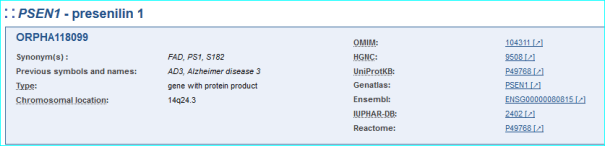

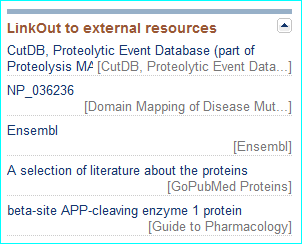

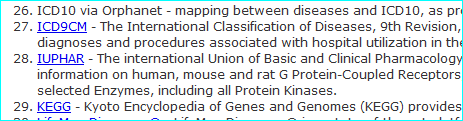

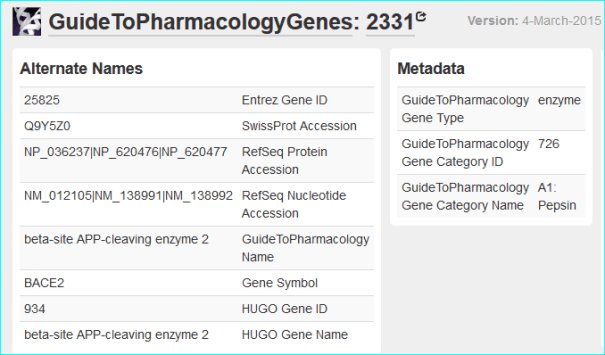

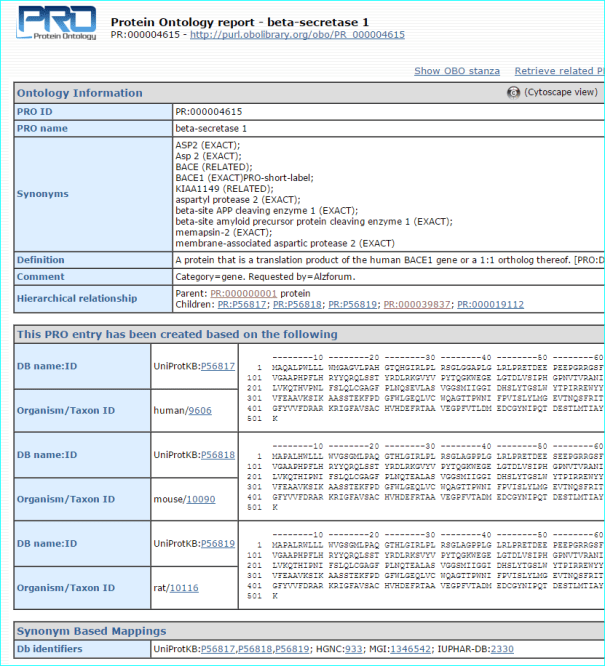

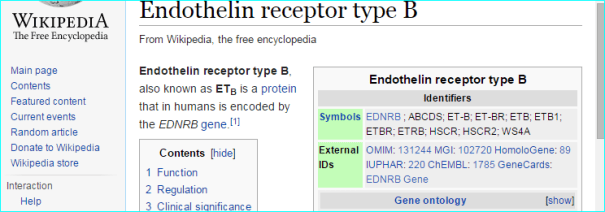

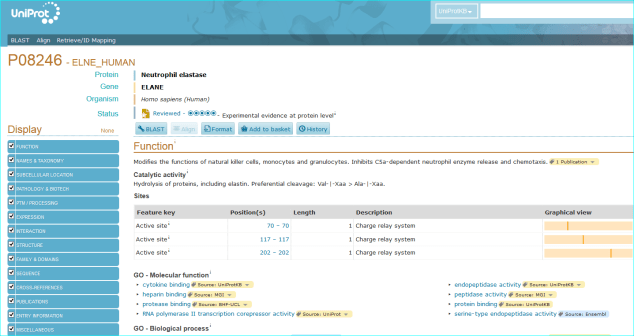

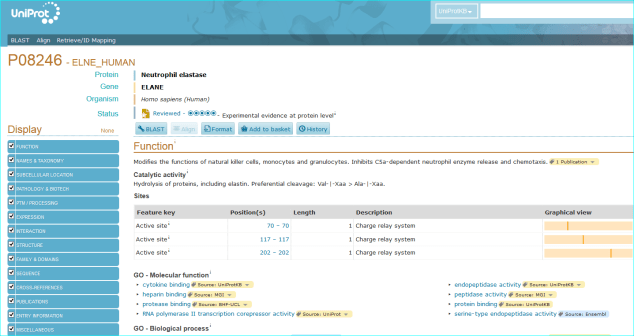

Protein. The use of standardised names and accession numbers to enable the resolution of “P” is more common than for “C” entities in papers. Nevertheless, ambiguity can still be a problem. As you can see in GtoPdb, we cross reference commonly used protein or gene identifiers, including our own NC-IUPHAR nomenclature. For many reasons we use the UniProt ID as an unequivocal, species specific, primary identifier, which, for human proteins, is the Swiss-Prot ID. We can also use the approved HGNC symbol. For those more familiar with the NCBI-world of annotation, a RefSeq NM or NP is aOK for us, but an Entrez GeneID is preferable. In cases where the paper specifies a protein complex you may be able to resolve this to the constituent subunit IDs (but we can check this). In the AZD9688 paper the protein name “Neutrophil Elastase” can be resolved to UniProt P08246.

It can also be identified as HGNC symbol ELANE, the Entre Gene entry 1991 and our own GtoPdb protein ID 2358. Note, as for many enzyme families with a history of alternative names, ELANE can be confused with five members of the chymotrypsin-like elastase family (CELA1, CELA2A, CELA2B, CELA3A and CELA3B). This includes what used to be called pancreatic elastase, that now splits into the last three gene names in the list.

Splice-variant specific pharmacology presents another challenge for molecular resolution (see PMID 24670145). For papers where this is highlighted, an iteration with the curation team is advised but note that Swiss-Prot includes published alternative splicing as numbered isoform cross-references with specific URLs. For a publication, the key question for annotating differential pharmacology (e.g. significantly different IC50 for splice forms) is that the experimental characterisation needs to be assignable to a single sequence-defined splice form.

Appendix I Direct entity mark-up from publishers

As exemplified in the British Journal of Pharmacology publications from NC-IUPHAR (e.g. PMID 24528243) the PDF and HTML versions include live links to GtoPdb for ligands and targets. Analogously, some journals provide direct links to PubChem. The first of these was Nature Chemical Biology that has now been followed by Nature Chemistry and Nature Communications. Some Elsevier journals now also include PubChem CID numbers and links.

Appendix II An outline of key structural specifications for chemical entities

Note that most chemistry tool-kits can execute the interconversions indicated by the arrows and major chemistry databases will pre-compute links between them. However, the round-tripping may not be perfect.

Note that most chemistry tool-kits can execute the interconversions indicated by the arrows and major chemistry databases will pre-compute links between them. However, the round-tripping may not be perfect.

Appendix III Peptides and radioactive analogues

Pharmacologically active peptides (as a “C” entity) present different NTS problems to small molecules. They require options of representation as three-letter codes or FASTA character string. In addition, endogenous unmodified peptides specifically cleaved from precursors are usually specified in the Swiss-Prot features lines (so you can send us the URLs for these). Many are also specified as SMILES in PubChem CIDs. Complications arise from names that may be not be IUPAC standard and/or include posttranslational modifications such as N-acetylation or C-amidation. Exogenous synthetic peptides have the same issues and may need to be iterated with us. Radioactively labelled analogues (small molecules or peptides) also feature prominently in the pharmacological literature. However, sometimes the molecular position of the label is unspecified. Here again, we have resolving approaches where may find them in PubChem but it would be useful if you have a suppliers catalogue reference.

Appendix IV Bulk extraction

A lot of time may be saved where compounds and proteins in a publication can be found either already marked-up and/or they can be extracted in bulk (i.e. for the entire document or sections therein) but only a few options can be noted here. PubMed Central runs its own Entrez look-up tagging for full text articles. Other automated options for genes and proteins include EBI Whatzit and Utopiadocs. For small molecules chemicalize.org is the most effective, particularly for IUPAC names. Note that Europe PubMed Central also includes entity mark-up for the abstract text and a Bio Entities tab. In addition there is a “HAS_CHEMBL:y” tag that can identify those publications extracted by ChEMBL with the entities marked up. This is focused on medicinal chemistry rather than pharmacology papers but note the latter may cite the former.

Appendix V Patents

In terms of global drug discovery output these contain more medicinal chemistry data than papers (see PMID 24204758). However, compared to journals, they are more difficult to mine. While tips for this cannot be included here, anyone interested in patent searching the context of new or existing GtoPdb content is welcome to contact us. Note we routinely cross-check sources such as SureChEMBL in the case of new clinical candidates to see what expanded SAR data sets may be available.